But whether they will change Vladimir Putin’s behaviour is another matter

IN LATE June Daimler, a German carmaker, broke ground on a new Mercedes-Benz plant north-west of Moscow. “We are confident in the long-term potential of Russia,” Markus Schäfer, a board member, said at the ceremony. The €250m ($296m) factory marked the first investment by a Western carmaker since America and the European Union slapped sanctions on Russia as punishment for its aggression in Ukraine three years ago.

After more than two years of recession, Russia is projected to return to growth this year. Until recently, the chill that sanctions put on the investment climate seemed to be thawing. “People had begun to forget about them,” says Chris Weafer of Macro-Advisory, a Moscow-based consultancy. But in late July America’s Congress voted to expand the sanctions. Vladimir Putin responded by demanding that America reduce its diplomatic staff in Russia by some 750 people. (Most of those affected are likely to be Russian employees.) He also shut down the American diplomatic dacha in Moscow’s Serebryany Bor forest—even the barbecues had to go.

The new offensive has revived arguments over whether sanctions work. Proponents say they helped stall Russia’s military intervention in Ukraine. Naysayers reckon they just let politicians look tough. The truth is more complicated. So far they have not changed Mr Putin’s behaviour abroad, and have helped him consolidate power at home. Yet in the long term they may undermine the stability of his rule.

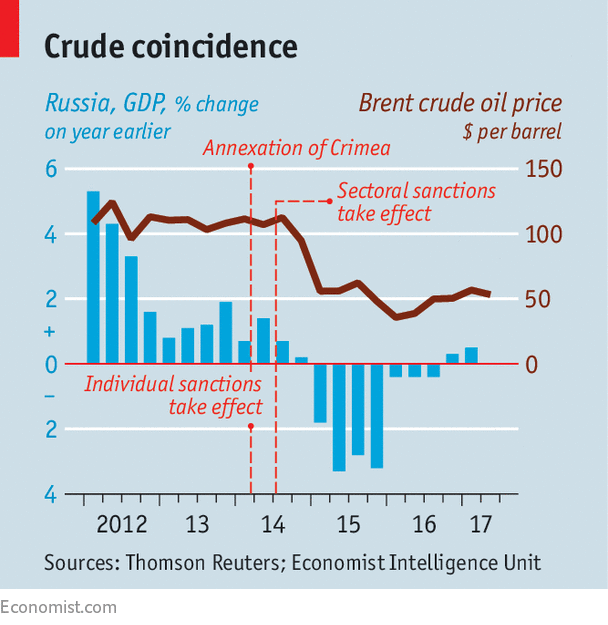

The first sanctions came in response to the takeover of Crimea in March 2014, and targeted individuals with travel bans and asset freezes. In July that year, as Russian-backed separatists rampaged in eastern Ukraine, “sectoral sanctions” followed, restricting credit to a host of Russian energy and defence firms and banks. The measures were calibrated to avoid rocking global markets and to win support from the European Union, which passed sanctions of its own. “The purpose was never to bring down the Russian economy,” says a former American official.

After the oil price collapsed in late 2014, Russia’s economy fell into crisis. Sanctions made things worse. A credit crunch led the government to dip into reserves to bail out banks and firms. Uncertainty made foreigners cautious about dealing with anyone in Russia, not just those on the lists. These “silent sanctions” chilled the business climate, says Natalia Orlova, chief economist at Alfa-Bank, Russia’s largest private bank. Foreign direct investment fell from $69bn in 2013 to just $6.8bn in 2015.

American officials seized upon this as proof that sanctions work. “Russia is isolated, with its economy in tatters,” President Barack Obama declared in January 2015. At the time Western leaders fretted that Russia might push deeper into Ukraine. Supporters of the sanctions argue that they helped prevent this, underpinning the signing of the Minsk peace agreements in February 2015.

Nonetheless, the sanctions have not altered Mr Putin’s strategy. Russia continues to support the separatist republics in Ukraine, and Crimea’s annexation has become a fait accompli. “The honest truth is that [sanctions] have yet to change their policies,” says Evelyn Farkas, the former Russia point person at the Pentagon. Russia went on to intervene in Syria and, in 2016, meddle in America’s elections.

At home, the government used the sanctions to blame the economic downturn on conniving foreigners. By cutting Mr Putin’s cronies off from global markets, sanctions “inadvertently made them more dependent on the Kremlin”, argues Andrew Weiss of the Carnegie Endowment, a think-tank. In 2015, according to the Russian version of Forbes, Arkady Rotenberg, Mr Putin’s judo buddy and a sanctioned construction magnate, received 555bn roubles’ worth of government orders. Sanctions became an object of public ridicule. A patriotic T-shirt captured the mood: a drawing of a nuclear missile captioned “The Topol is not afraid of sanctions.”

With time, business came to fear them less, too. In 2014 United States Treasury officials warned American companies off attending the St Petersburg International Economic Forum, Russia’s equivalent of Davos. By 2016 many CEOs had returned. Russia successfully placed a $1.25bn sovereign Eurobond in September 2016, with more than half bought by Americans. The United Nations reckons that 280 greenfield investment projects in Russia in 2016, below the ten-year peak of 596 announced in 2008, but an improvement over the nadir of 194 in 2014. IKEA, Leroy Merlin, Pfizer and Mars Inc all have plans for stores or factories.

The new sanctions may give foreign investors pause. That worries the Kremlin. As Mr Putin looks towards his fourth term (he is expected to win next year’s election), Russians are more concerned with their wallets than with Crimea. Growth this year is projected to be 2% or less. For the elite, the prospect of long-term stagnation and endless standoff with the West raises questions about the country’s direction. “The sense of an historic dead-end evokes panic,” writes Vladimir Frolov, a Russian analyst. Sanctions will not cause Mr Putin to reverse course, but they do make it harder for him to drive his way out.

Image: © AP Photo, Evan Vucci